An Orthodox Critique of the Theology of Election & Secessionism

See the following Links to read and study the works of Reformed Calvinist Theology:

What Is the Theological Idea of “Election”?

Election is a word we find in the Bible that means God choosing someone or something for a special purpose. It doesn’t mean God plays favorites or that He doesn’t love everyone — it means He gives some people a special job or mission in His big story.

Imagine This: A Birthday Party Invitation

Let’s say you are planning a big birthday party. You can’t invite the whole world, but you send invitations to a few of your closest friends. You choose them not because they are better than everyone else, but because you want them to be part of your special day. That’s kind of like God’s election — He invites some people to come close to Him, to know Him, and to be part of His big plan.

Examples from the Bible

- Abraham – God chose Abraham to start a whole new family, called Israel, through whom the whole world would be blessed (Genesis 12:1–3).

- Israel – God chose the people of Israel, not because they were the best or biggest, but because He loved them and had a plan to bless others through them (Deut. 7:7–8).

- Jesus – God chose Jesus to save the world (John 3:16). He’s the most important part of God’s election.

- The Church – God chooses people today to follow Jesus, live in His love, and help others find Him too (Ephesians 1:4–5).

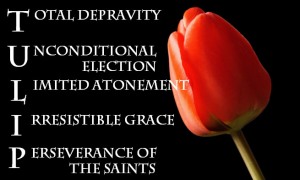

The Calvinist doctrine of election is one of the most debated and nuanced teachings in Christian theology. Rooted in the Reformed tradition, it holds that God sovereignly chooses some individuals for salvation (the elect), not based on any foreseen merit or action on their part, but solely because of His will and grace. This doctrine is most clearly articulated in John Calvin’s writings and later codified in the Synod of Dort (1618–1619).

Key Scriptures:

- Ephesians 1:4–5 – “He chose us in Him before the foundation of the world… having predestined us… according to the good pleasure of His will.”

- Romans 9:10–24 – Paul explains that God chose Jacob over Esau “before they had done anything good or bad,” emphasizing divine choice, not human merit.

- John 6:37, 44 – “All that the Father gives me will come to me… No one can come unless the Father who sent me draws them.”

🧭 Real-Life Impact: Why This Matters

Evangelism & Missions

Arminianism: Emphasizes human response, which often fuels a deep urgency in evangelism — since every person has a real chance to accept or reject Christ.

E.g., John Wesley and most Pentecostal and Methodist movements follow this model.

Calvinism: Believes God has already chosen who will be saved, but evangelism is the means God uses to bring the elect to salvation. This view often produces boldness, knowing that success doesn’t depend on human persuasion, but on God’s power (cf. Acts 18:10).

E.g., Charles Spurgeon, George Whitefield, and William Carey (the father of modern missions) were Calvinists.

Both views champion mission, but from different angles: Calvinists trust God’s sovereignty; Arminians press human responsibility.

Assurance of Salvation

- Calvinism: Offers strong assurance — if you are truly saved, God will keep you to the end. This leads to deep rest and confidence in God’s faithfulness.

- Arminianism: Believers must remain faithful and can fall away. Assurance comes not from an unchangeable decree but from continuing in Christ daily.

Discipleship & Spiritual Formation

- Calvinist discipleship focuses on God’s transforming grace, sanctification as evidence of election, and spiritual growth rooted in God’s promises.

- Arminian discipleship focuses on active cooperation with grace, daily surrender, and ongoing personal responsibility to remain faithful.

God’s Character and Justice

Arminianism: Elevates God’s fairness and universal love — that Christ died for all, and everyone gets a genuine opportunity to be saved.

Critics: It can seem to limit God’s power or make salvation depend too much on human effort.

Calvinism: Elevates God’s sovereignty and mystery. Salvation is entirely God’s doing, emphasizing His right to show mercy as He pleases (Rom. 9:18).

Critics: It can seem to make God arbitrary or unloving toward the non-elect.

So Which Is Right?

Both systems aim to uphold Scripture, but focus on different aspects of God:

- Calvinism: God’s sovereignty, glory, and grace.

- Arminianism: God’s love, justice, and invitation.

Metaphor: The Door of Salvation

- From the outside, the door says: “Whosoever will may come” (Rev. 22:17).

- Once inside, you look back and read: “Chosen in Christ before the foundation of the world” (Eph. 1:4).

This poetic picture reminds us: God is sovereign, and humans are responsible — and how those two truths meet is a sacred mystery.

John Wesley - Methodist Critique

In his famous sermon “Free Grace” (1740), John Wesley offered a sharp critique of the Calvinist doctrine of unconditional election, which he believed undermined the character of God and the moral responsibility of humanity. He presented seven key objections to the doctrine. Here they are, summarized:

1. It Makes God Unjust

Wesley argues that unconditional election portrays God as acting arbitrarily, choosing some for salvation and passing over others without regard to their moral choices. This, he claims, contradicts God’s justice.

“It represents God as worse than the devil: as both more false, more cruel, and more unjust.”

2. It Destroys God’s Mercy

If God elects only a few to be saved and leaves the rest to eternal damnation without any choice or opportunity, then God is not truly merciful, Wesley insists.

“You represent Him as a God who is not even merciful to all His works.”

3. It Makes God the Author of Sin

Wesley insists that if some are predestined to damnation, then God must be responsible for their sin and unbelief — a view he sees as blasphemous.

“You make Him the author of sin, whether you will or no.”

4. It Overthrows the Scriptural Call to Holiness

If election is unconditional, Wesley asks, then why pursue holiness or good works at all, if one’s fate is already sealed?

“You say, ‘I am elect; and therefore I shall be saved:’ and what need of holiness?”

5. It Discourages Preaching and Evangelism

If only the elect can be saved, then preaching the gospel to all people becomes pointless. Wesley sees this as an attack on evangelistic fervor.

“It destroys the comfort of religion, the happiness of Christianity, and the very foundation of all Christian service.”

6. It Damages Christian Assurance and Leads to Despair

Believers may doubt their salvation, wondering if they are truly among the elect, leading to spiritual anxiety or despair.

“If I am not elect, I must perish; and if I am, I shall be saved whether I will or not.”

7. It Is Not Supported by the Bible or Early Church

Wesley maintains that unconditional election is not consistent with the broader teaching of Scripture nor with the historic consensus of the early Church Fathers.

He upholds that Scripture repeatedly calls all people to repentance and faith, indicating universal grace, not limited election.

The Orthodox Critique

Calvinism and Eastern Orthodoxy represent two radically different theological traditions. Orthodoxy has its roots in the early Ecumenical Councils and the Church Fathers, whereas Calvinism emerged as a reaction to medieval Roman Catholicism. Aside from a brief encounter in the early seventeenth century, there has been very little interaction between the two traditions.

1. Total Depravity

Calvinism teaches that humans are completely corrupted by sin and thus incapable of choosing God without irresistible grace.

Orthodox View: While acknowledging the impact of the Fall, Eastern Orthodoxy maintains that humans still possess the image of God and the capacity for free will. The human will is wounded but not destroyed, allowing for cooperation with God’s grace in the process of salvation.

John of Damascus (c. 675–749 AD):

“Man’s free-will was corrupted by sin, but not destroyed.” (Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, NPNF Vol. IX)

Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335–395 AD):

“The will… cannot be enslaved, being the power of self-determination.” (The Great Catechism)

Cyril of Jerusalem (c. 313–386 AD):

“The soul is self-governed… endowed with free will.” (Catechetical Lectures 4.18)

Irenaeus of Lyons (c. 130–202 AD):

“Man is in his own power with respect to faith.” (Against Heresies 4.37.2)

Justin Martyr (c. 100–165 AD):

“He both persuades us and leads us to faith.” (First Apology 10)

2. Unconditional Election

Calvinism teaches that God elects some to salvation and others to damnation apart from foreseen merit or response.

Orthodox View: This concept is seen as incompatible with the belief in a loving and just God. Eastern Orthodoxy emphasizes synergism—the cooperation between divine grace and human free will. Salvation is available to all, and individuals have the genuine freedom to accept or reject God’s offer.

Gregory Palamas (c. 1296–1359 AD):

“God does not decide what men’s will shall be… He foreknows and thus foreordains—not by will but by knowledge.” (Chapters, MPG 150, 1192A)

John of Damascus:

“While God knows all things beforehand, yet He does not predetermine all things.” (Exposition, NPNF Vol. IX)

3. Limited Atonement

Calvinism teaches that Christ died only for the elect, not for all humanity.

Orthodox View: This view is considered to limit the universality of Christ’s redemptive work. Eastern Orthodoxy teaches that Christ died for all humanity, offering salvation to everyone, though not all may choose to accept it.

St. John of the Ladder (c. 579–649 AD):

“God belongs to all free beings… the salvation of all—faithful and unfaithful, just and unjust…” (The Ladder of Divine Ascent, Step 1)

Irenaeus of Lyons:

“Christ came… for all men altogether, who from the beginning… feared and loved God.” (Against Heresies 4.22.2)

Orthodox Liturgy (St. John Chrysostom):

“He gave Himself for the life of the world… for He alone is good and loves mankind.”

4. Irresistible Grace

Calvinism holds that God’s saving grace cannot be resisted; it always accomplishes its purpose.

Orthodox View: This doctrine is perceived to undermine human freedom. In Eastern Orthodoxy, grace is seen as a gift that requires human cooperation. Individuals can resist or accept God’s grace, preserving the integrity of free will.

St. Kallistos Ware (1934–2022):

“Where there is no freedom, there can be no love… God can do everything, except compel us to love Him.” (The Orthodox Way, p. 76)

Letter to Diognetus (2nd Century):

“He willed to save man by persuasion, not compulsion; for compulsion is not God’s way of working.” (7.4)

5. Perseverance of the Saints

Calvinism teaches that those who are truly elect will inevitably persevere in faith to the end.

Orthodox View: While affirming the necessity of perseverance, Eastern Orthodoxy warns against presumption. Salvation is a dynamic journey requiring continual faith and repentance. Assurance of salvation is not absolute, as individuals can choose to turn away from God.

Confession of Dositheus (1672) (Orthodox synod rejecting Calvinism):

“Particular grace… co-operating with us… justifies us, and makes us predestinated.”

Irenaeus of Lyons:

“Man… making progress day by day… should recover from the disease of sin… and being glorified, should see his Lord.” (Against Heresies 4.38.3)

The Orthodox Church rejects the Calvinist TULIP because it:

- Distorts God’s love, making it partial and arbitrary

- Denies the true nature of free will

- Misrepresents the scope of Christ’s atonement

- Undermines the synergy between God and humanity in salvation

- Contradicts the consensus of the early Church Fathers and the Seven Ecumenical Councils

Conclusion

Arakaki concludes that the TULIP framework presents a deterministic view of salvation that conflicts with the Eastern Orthodox understanding of a synergistic relationship between God’s grace and human freedom. The Orthodox tradition emphasizes the transformative process of theosis (becoming one with God) through cooperation with divine grace, preserving both God’s sovereignty and human responsibility.

The Pentecostal Critique

Comparison between the respective views of John Calvin and classical Pentecostals on the role of the Holy Spirit in reading the Bible. Dr Marius Nel

Classical Pentecostals accept that respect for the authority of the Bible as the word of God requires meticulous attention to unlock the meaning that biblical passages held for original hearers and readers as a condition for understanding its meaning for contemporary readers (Zuck 1984:120). Because the Holy Spirit plays a prominent role in the inspiration of the original text and the illumination of the text to contemporary readers, Pentecostals emphasise the importance of leaving ample room for the work of the Spirit in biblical interpretation; the Spirit is the true expositor of the word of God.

An in depth Study of why Pentecostals are Against Calvinism:

Roger E. Olson’s book Against Calvinism: Rescuing God’s Reputation from Radical Reformed Theology (Zondervan, 2011) is a robust and accessible critique of five-point Calvinism (TULIP), particularly as developed in neo-Reformed circles. Olson does not reject God’s sovereignty—but argues that Calvinism’s version of sovereignty distorts God’s character, contradicts Scripture, and undermines moral responsibility.

Here is a summary of Olson’s main critiques of Calvinism:

1. God’s Character Is Maligned by Calvinism

Olson’s central concern is that Calvinism makes God morally monstrous. He objects to the idea that God predestines some to eternal damnation (double predestination) for His glory:

“Any theology that says God ordains sin and suffering for his glory makes God indistinguishable from the devil.”

He sees this as incompatible with the biblical picture of God’s goodness, love, and justice.

2. Unconditional Election Undermines Human Responsibility

Calvinism teaches that God chooses who will be saved and who will be damned, without regard to anything the person does. Olson argues this destroys any real concept of human freedom and moral accountability.

“If God determines everything, then humans are not truly responsible.”

3. Limited Atonement Denies God’s Universal Love

Olson finds the doctrine of limited atonement (that Jesus died only for the elect) especially troubling, as it contradicts passages like John 3:16 and 1 Timothy 2:4, which speak of God’s desire to save all people.

“Calvinism, taken to its logical conclusion, teaches that Jesus did not die for most people.”

4. Irresistible Grace Turns God into a Puppet Master

Olson argues that if grace is truly irresistible, then faith is not really faith — it is coerced compliance. He insists that genuine love and trust must be freely chosen.

“True relationship requires freedom; irresistible grace undermines love.”

5. Perseverance of the Saints Encourages False Assurance

While Olson believes in eternal security, he critiques the Calvinist version of perseverance which teaches that if someone falls away, they were never truly saved. He sees this as pastorally damaging and prone to spiritual arrogance or fear.

6. Scriptural and Historical Problems

Olson claims that many Scriptures contradict Calvinism, especially those affirming human choice and God’s universal offer of salvation. He also argues that Augustine was the first to introduce double predestination—and the early church fathers did not teach it.

7. Calvinism’s God Is Arbitrary and Untrustworthy

Perhaps Olson’s most provocative point is that Calvinism redefines God’s goodness in ways that are not recognizable from Scripture. If God decrees evil for His glory, Olson argues, then God becomes morally incoherent.

“God does not need to damn some in order to glorify Himself through saving others.”

8. Theological Determinism Is Not Biblical Sovereignty

Olson distinguishes between sovereignty and determinism. He believes Calvinists equate God’s sovereignty with meticulous control over all things, including sin, which he finds incompatible with biblical freedom and responsibility.

Olson’s Alternative: Arminianism

Olson offers a classical Arminian perspective:

- God sovereignly gives humans real free will.

- Christ died for all, and salvation is available to all.

- Grace is resistible, and believers must persevere in faith.

- God’s sovereignty is best understood as relational and redemptive, not deterministic.

⚠️ Another Radical Belief!!!

Carlton Pearson’s “Gospel of Inclusion” is a radical reinterpretation of traditional Christian doctrine, especially regarding salvation and hell. His theology claims that all people are already saved through Christ, regardless of whether they’ve heard the gospel or made a personal confession of faith. Though many orthodox scholars find his exegesis strained or out of context, Pearson appeals to several key Scripture passages to support his inclusive message.

Below is a summary of the main Bible verses he uses and how he interprets them:

John 3:16 “For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have everlasting life.”

He emphasizes the phrase “God so loved the world” to argue that God’s love extends unconditionally to everyone, not just believers. He tends to downplay the conditional “whoever believes” part, interpreting it more as a present-tense awakening to an already-given salvation than a requirement for inclusion.

1 Timothy 2:4 “[God] desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth.”

If God desires all to be saved—and God is sovereign—then all will be saved. He argues that it would be unjust or contradictory for an all-loving, all-powerful God to eternally torment anyone whom He wants to save.

1 John 2:2 “And He Himself is the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not for ours only but also for the sins of the whole world.”

This verse is central to his claim that Christ’s atonement is universal in scope and unconditional in application. He sees this as evidence that no one is left out of God’s saving plan.

Romans 5:18 “Therefore, as through one man’s offense judgment came to all men, resulting in condemnation, even so through one Man’s righteous act the free gift came to all men, resulting in justification of life.”

He uses this verse to support a doctrine of universal justification: if Adam’s sin affected all, then Christ’s righteousness redeems all—without exception.

Philippians 2:10–11 “That at the name of Jesus every knee should bow… and that every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.”

He interprets this as a future universal confession, not under compulsion, but as joyful acceptance. He suggests that eventually everyone will freely acknowledge Christ, even if not in this life.

1 Corinthians 15:22 “For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive.”

He reads this literally: just as all humanity fell in Adam, all will be restored in Christ, regardless of faith or repentance.

Luke 15 – The Parable of the Prodigal Son

He sees the father’s unconditional acceptance of the wayward son as a picture of God’s universal mercy—no punishment, no prerequisites, just restoration.

Acts 10:34-35 “God shows no partiality. But in every nation, whoever fears Him and works righteousness is accepted by Him.”

He uses this to argue that people of all religions and cultures who pursue truth or goodness are already accepted by God—even without conscious belief in Christ.

2 Peter 3:9 “The Lord is… not willing that any should perish but that all should come to repentance.”

He argues that God’s will cannot be thwarted, and since God wills salvation for all, all will eventually be saved—even if through a process of spiritual awakening beyond this life.

Orthodox and Historical Christian Response:

Bishop Carlton Pearson was once a prominent Pentecostal-Charismatic evangelist and megachurch pastor in the U.S., closely associated with the Oral Roberts and Word of Faith movements. However, in the early 2000s, he publicly rejected core evangelical doctrines—most notably eternal conscious punishment in hell—and embraced a belief he called “The Gospel of Inclusion.” (Carlton Pearson’s story was dramatized in the 2018 Netflix film “Come Sunday”, starring Chiwetel Ejiofor, which portrays his theological crisis and rejection by the evangelical community.)

In 2004, the Joint College of African-American Pentecostal Bishops declared Pearson’s views heretical. His Tulsa megachurch, Higher Dimensions, dissolved, and he was labeled a “heretic” by many in the evangelical world.

He later found a home in progressive mainline churches, such as the United Church of Christ and All Souls Unitarian Church in Tulsa.

Most Church Fathers and traditional theologians agree that God desires all to be saved (cf. 1 Tim 2:4), but they affirm that:

- God’s love requires free response (synergy), not automatic inclusion;

- Faith in Christ, as revealed and confessed, is the normative path to salvation;

- Hell is real and eternal separation from God is a tragic possibility for those who reject grace.

The Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant consensus warns against redefining clear teachings on repentance, judgment, and free will in light of subjective interpretations.